DEREK PRINGLE

@derekpringle

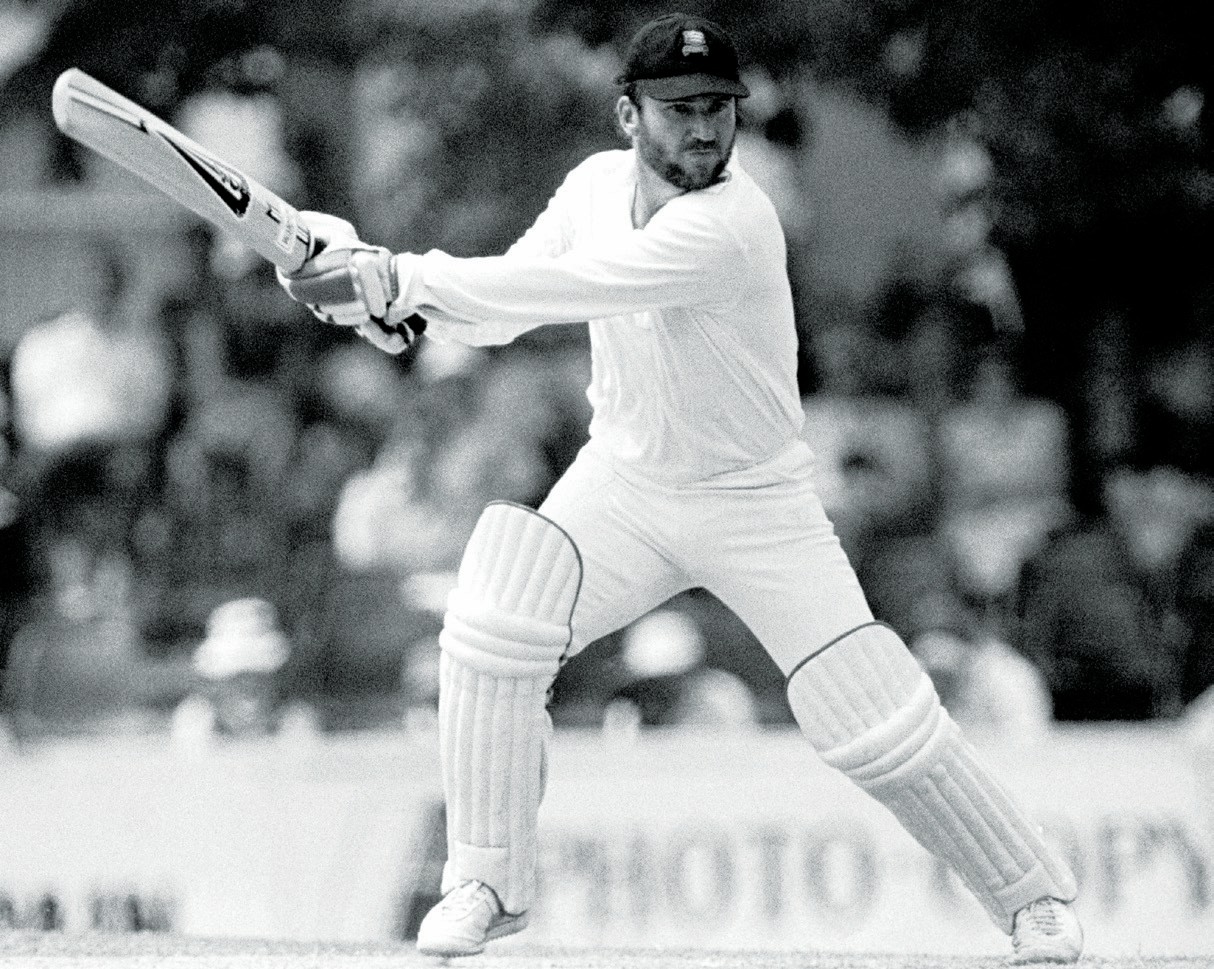

Allan Border was an uncompromising cricketer but even he took that to extremes in 1986 at Ilford’s Valentines Park. There, on a pitch with much of its surface worn away, he made 56 of the bravest runs I’ve seen, nearly winning a game for Essex that Hampshire assumed was theirs the moment Malcolm Marshall’s thunderbolts burst through the top on the final day.

Border batted without a helmet and took numerous, painful body blows from Marshall, by then a West Indies regular and the fastest bowler in the world. These were not bouncers but 90mph balls rearing from a good length which could not be avoided. His skill and bravery, literally putting his body on the line, made a huge impression on the dressing-room. Chasing 198, Essex lost by 12 runs, but it rammed home that no cause was ever lost, a guiding principle to us winning the Championship that season.

I mention this because Border and Marshall were overseas players whose value went way beyond the runs and wickets they contributed, substantial though they were. Both Essex and Hampshire had ways of playing, philosophies if you like, that those two continued to shape, something you can’t say about many of today’s overseas pros, who barely stay long enough to know their teammates’ names, let alone how they think.

A quick head count so far reveals there have been 85 overseas players signed by counties this season for the Championship, T20 Blast and the One-Day Cup competitions. The Hundred, which is different vinegar and which has its own rules and economy, is not included. Incredibly, Durham account for seven of those overseas pros, some of whom breeze in for just a few games. The overall figure is large enough to power seven extra teams in the Championship, a scandal given the amount it must be costing a game which forever claims to be cashstrapped, at least at the domestic level.

I’d always assumed, perhaps naively, that teams signed overseas players to boost competitiveness, add some stardust, and fill a particular role none of the homegrown players are quite up to. On that basis, imported players should always head their team’s averages, or at least be in the top two bowling or batting – something true at only eight of today’s 18 first-class counties.

Border comfortably topped Essex’s batting averages back in 1986 and was second only to a rampant Graham Gooch in 1988, his only other season at the club. Marshall, who played 11 years for Hampshire, headed their bowling averages for all but one of those years. Which suggests the majority of today’s counties are not getting much bang for their buck. But if they are not purchasing excellence, and in Marshall’s case excellence over a long period, what exactly are they getting?

This is where the picture gets murky. Before Brexit most counties had Kolpak players on their staffs who, due to a treaty their countries had with the European Union, could play as home-qualified players in county cricket. Feelings about them were mixed; advocates believing they raised standards, critics that they stifled local talent.

Simon Harmer at Essex was a Kolpak but since Brexit has become an overseas player, albeit one fully invested in the club for whom he plays all three formats. Unlike many of today’s overseas influx he is a master of his discipline, spin bowling, and one of the few worth the money his county has invested in him.

There are other quality players involved such as Marnus Labuschagne at Glamorgan and Steve Smith and Cheteshwar Pujara at Sussex, though it perhaps suited the first two to get in some practice before the Ashes. But they are the exception.

With Kolpaks no more, the ECB has lowered the entry bar for overseas players trying to access county cricket. Instead of having to play a combination of 15 ODIs or T20s over previous two years, or one Test over the previous year, as used to be the case pre-Covid, players have only to play 20 T20 matches in an ICC full member country within the past three years to qualify. Inevitably, a reduction in quality, especially in red ball cricket, has occurred.

Not that excellence is especially prized any more, which sounds daft I know. More useful to counties these days is the overseas player who won’t be selected for his country, or The Hundred, or the numerous T20 Leagues now encroaching on the northern summer, over which English cricket once had a monopoly. Those players offer uninterrupted availability, which is attractive, but by a process of elimination aren’t going to be much good. Yet counties still sign them, that smidgen of exotica ticking the box named ‘ambition’ as demanded by members and sponsors.

It must be dispiriting for young, homegrown talent to see some of the third-rate overseas players now plying their trade in county cricket. One of the attractions of the One-Day Cup these past two years, in its supposedly graveyard shift alongside The Hundred, has been for club members to see young players they wouldn’t normally watch. And yet some counties, including Essex, have signed overseas players to take part specifically in that competition, thus denying more of their fledgling talent (they are currently playing two 18-year olds) its big moment, which seems myopic.

Most counties aren’t contrite. One administrator told me that developing a young player is a five-to-seven year project and that the club’s commercial partners don’t have the patience for that. He did baulk at the cost of overseas players, though, indicating that just the air flights for two they signed before the pandemic, plus families, came to £40,000, which is a young player’s salary. And that before any pay or accommodation costs were shelled out.

Then there’s the county coaches and directors of cricket, their jobs often on the line, looking for the quick fix that can theoretically be offered by an overseas player but not a young squad member. And therein lies the problem. Clubs put their resources (coaches, signings, contracts etc) into performance and not development, the concept of building a team, over a season or two, being entirely alien.

The overseas players who played county cricket during the late 70s and 80s were the greatest talents of their generation. They raised standards of county cricket to arguably the highest they’ve ever been. But that talent, or its equivalent, is no longer available. Protective home boards, as well as lucrative T20 tournaments on every continent, keep them away, which means there’s been a vertiginous drop in quality.

Should we care? Some will say England’s Test team is motoring along nicely while we are double world champions in the two white-ball cups. But I reckon there’s a lag with trouble coming down the track, at least in red-ball cricket. In a part of the game where resources are never plentiful I’d rather finite resources were spent on the future rather than plugging problems in the here and now, unless counties can attract the very best and for more than just a few games.