The seeming prevarication over the future of Alastair Cook as England captain seems to be based on achieving the right level of sensitivity and timing for what is a major event, though it didn’t always use to be like that. Rewind 30 years to the 1980s and just about any England defeat saw the captain’s head end up on a silver platter with indecent haste.

It may be that the current rumination means that Cook is staying on as Test captain, but that would mean all the clues – the revealing interview he did before the series in India, the spent body language in Chennai during the last Test, the “Joe Root is ready” eulogy – were all red herrings.

There seems to be an obsession these days that you can micromanage change in order to remove the negative emotions but life, especially in sport, is not like that. As Steve Waugh, Australia’s gimlet-eyed captain, was fond of saying during his playing career: “There are no fairy tales in cricket” – a sentiment with which every England captain between 1980-90 would concur.

If that decade was particularly brutal on its England captains, then this one has generally sought to soften any body blows, though the removal of Cook as one-day captain, just a few weeks before the 2015 World Cup, was a throwback to more ruthless times. Perhaps the indignity of that is what drives this careful approach now, Cook having given the captaincy his all despite lacking the telling flourishes and shrewd man- management of a great leader.

Whatever the decision on Cook, it will only be made after he has held discussions with Andrew Strauss, the director of England cricket. There was no forum like that back in the 80s. Then, the only courtesy shown was that of a phone call from the chairman of selectors informing a captain of his fate. But then expectations of being treated well were not high. As David Gower once joked after taking the fateful call – “I felt grateful they had not reversed the charges.”

Given this was in the days before mobile phones, the news was not always delivered in private. When Keith Fletcher was informed by Peter May that he was to be replaced by Bob Willis in 1982, he was at home but immediately jumped in his car to drive around for a few hours to allow his anger to dissipate, before returning to his wife and young daughters.

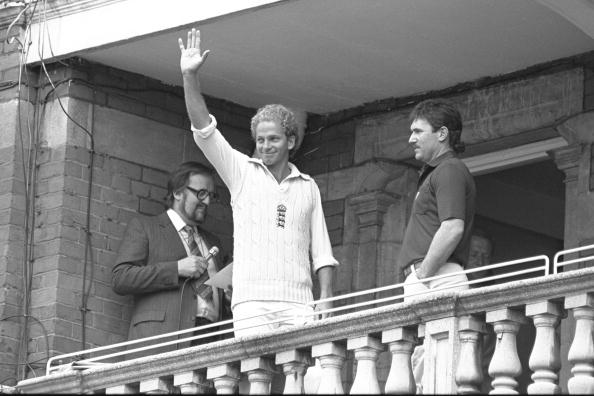

Four years later, Gower, who succeeded Willis, threw the “I’m in Charge” T-shirt he had made (as a joke) to Mike Gatting on the Lord’s balcony, after his team had lost the first Test to India. Prior to that defeat, Gower, who had just suffered a second whitewash by the West Indies under his command, knew he was on borrowed time. Even so, this was a very public transference of power completely at odds with how things are done now.

Gatting was, of course, replaced a few years later himself after being embroiled in a scandal involving a barmaid during the first Test of the 1988 home series against the West Indies. It might just as well have been 1528 though as the selectors, in an act of contrariness Henry VIII would have been proud of, got through another three captains in the four remaining Tests – all of them lost.

The effect on the team was a bewilderment bordering on black humour, though there were not that many players common to each team under a new leader. With no central contracts, England players only became close to one another on tour, not during home series. Appointing four captains during a five-match series is unprecedented in cricket history, though, which may explain why the England and Wales Cricket Board have gone so far the other way now.

Graham Gooch was the man in possession at the end of that series against the West Indies, but with the winter tour cancelled and a new chairman of selectors, Ted Dexter, he was not in charge by the time the Ashes began the following summer.

If he was disappointed he never showed it, but then it was his way to reveal little of himself except with bat in hand. He’d probably got an inkling though when Dexter, upon being asked of Gooch’s suitability to lead England, had said that “being captained by him would be like being slapped in the face by a wet fish”.

That said, Gatting was duly appointed instead only for the decision to be rescinded by the chairman of the Board, Ossie Wheatley, the only person who possessed the right to veto an England captain. As Gatting fumed, Gower, whom he had replaced three years earlier, was reappointed. The return was not long lived and, after losing the Ashes, Gower resigned and the captaincy was returned to Gooch, a job he’d originally got by being about the last man standing.

With Dexter forced to eat humble ‘fish’ pie, Gooch, in concert with Mickey Stewart the coach, helped to forge a team where continuity meant more than playing two consecutive Tests. With hard work at its core, and the defeatism of the previous decade cast aside, Gooch’s England team generally gave a good account of itself. Only against the Aussies did they falter badly otherwise they competed well, even excelling in one-day cricket.

Gooch’s tenure lasted just under four years before being ended by one Ashes defeat too many. That term, of four to five years, is roughly how long modern England captains last before mission creep takes its decisive toll. After Gooch, Michael Atherton, Nasser Hussain, Michael Vaughan and Andrew Strauss, with a few interim captains in between, all did the job for that period of time.

Having done the same, Cook is at that point, having given it his all, where the natural laws say it is time for someone else to take the burden. And there is no shame in that.

This piece originally featured in The Cricket Paper, January 13 2017

Subscribe to the digital edition of The Cricket Paper here

Seem to remember at some point during that ‘four captains’ series that at one point Pringle himself was captain for a short time because whoever was in charge for that particular match had left the field.

Is that correct?